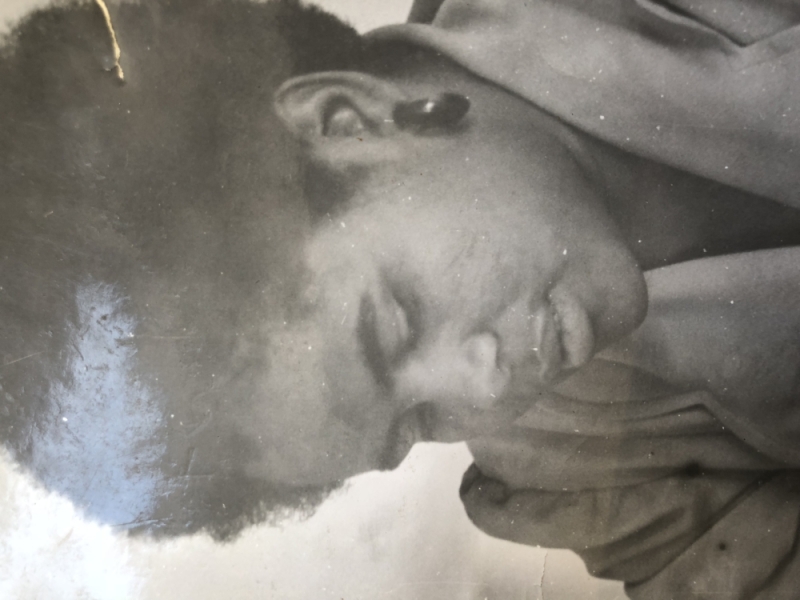

Venson-Moitoi: The intrepid Mmegi editor

Lesang Maswabi | Monday May 6, 2024 06:00

That institution would evolve into a reputable title called Mmegi, The Reporter towards the late 80s and today’s media giant of the 21st century just called Mmegi with a slogan, 'News we need to know daily' Venson-Moitoi became the newspaper’s first woman editor in 1971-73, immediately after completing her form-five (5) at Swaneng High/Secondary School in Serowe in 1970 at a young age of just 20 years. “I first went for a journalism course at the Africa Literature Centre that was run by the Mindolo Ecumenical Centre in Kitwe in early 1971, which was followed by an attachment at Zambia Daily newspaper in Lusaka later the same year”, says Venson-Moitoi.

She vividly recalls being arrested by the Ian Smith’s Rhodesian Police on her way back to Botswana then. Asked about their staff contingent then, Venson-Moitoi says she recalls working with a staff of five – herself, a typist called Kentahetse Mokalake, two printers Super Pilane, an American volunteer-teacher by the name of Turner and the late Patrick van Rensburg as the manager.

She recalls that in those olden days, as the sole editor and photographer, she had to do everything. She says: “That included covering and reporting stories, taking photographs and developing them, doing layout and even assisting in printing.” Produced under very challenging circumstances without enough resources or lack thereof, she says the then A4 size and 8-16 page publication only circulated mostly in Serowe and around the Central District. “The newspaper then also used to carry a feature on Ujamaa villagers in Tanzania to carry a spirit of Ipelegeng (self-reliance) that was vigorously being pursued by the government here. We had very limited resources, with advertising (commercial) clients ranging from only a few businesses like general dealer B. Wells Woodford, retail shop GB Watsons and Dennis Service Station,” reveals Venson-Moitoi.

These trading places also happened to be Mmegi Wa Dikgang’s selling points. She says wittingly, that in those heady-days, “it was probably easier to drive to Mahalapye from Serowe than trying to call. Although she does not quite recall the print-run, she recalls the newspaper’s weekly and sometimes fortnightly frequency. She attributes lack of support in advertising and readership (newspaper sales/circulation) to the villagers who had misguided opinion about van Rensburg whom they had regarded as a communist. Thus the community had perceived him to be on an indoctrination mission. “Mathata gape e ne ele go tlhoka go bala ke bagaetsho mo gae (Problem with the villagers was illiteracy) as most would just turn to the pictures, the adverts and cartoons for entertainment”, Venson-Moitoi says. Explaining how she had always been interested in writing as a vocation soon after her secondary school studies, Venson-Moitoi reminisces: “Not only did I usually assist Kibble White translate vernacular folk tales (mainane a Setswana) to English, but I had previously won a Secondary School national competition on short story writing.

The folk stories we translated were later published by McMillian in the early 70s. My other material had at around the same time been published at Botswana’s Information and Broadcasting’s Kutlwano magazine by the late Paul Rantao. I was also at some stage been a member of the school’s Art-Club, also active at the Library and a friend of a great writer of our time, Bessie Head, who had arrived in Serowe from South Africa in the mid 60s. It would seem trouble with the law-enforcement always followed Venson-Moitoi wherever she went in the region, including even in her own home-country, Botswana. She says: “Shortly after being arrested and declared a Prohibetd Immigrant in Rhodesia in 1971, which was followed by my husband and I being declared persona-non-grata in South Africa in 1975, Mmegi Wa Dikgang would soon be caused to close by the then government of Botswana.” All this because the newspaper had written a story after being tipped-off about a Boer woman who had been hired by the Botswana government to work as a Social Worker in Francistown to cater for South African refugees.

In one of the special publications from the past, when Mmegi celebrated 10th Anniversary in 1994, Venson-Moitoi is quoted as saying: “Technical problems aside, the newspaper soon found itself at loggerheads with the government. In particular the question of refugees from neighbouring countries of Zimbabwe, Namibia, South Africa and Angola came to the fore. Apparently, there were some within the refugee community who felt the government’s action was uncalled for in holding them in prisons and then repatriating them back to their countries and into the political situations they had tried to escape. Mmegi Wa Dikgang for some time ran their comments and likewise attempted to solicit for some response from government on the matter. It appears the government was not impressed with the paper and the interest it was developing on the subject.” She adds: “The newspaper then was funded by the All Africa Council of Churches through the Botswana Council of Churches (BCC).

Following an editorial carried on the refugee issue, the BCC would write to Mmegi, suggesting that the paper was inciting animosity against government. Soon after, our offices were paid a visit by the then Deputy Commissioner of Police (all the way from Gaborone) and Serowe Station Commander.” Without explanation, she declared that they received a letter to say they were not registered with the General Post Office, upon which her meek boss and Mmegi founder Patrick van Rensburg would quickly yield and pay a R500. 00 charge. That fine would also lead to collapsing the operations since the highest paid employee, was not even paid R50.00 per month! The paper could not afford it. “After Mmegi Wa Dikgang closed,” Venson-Moitoi continues, “the then Director of Information and Broadcasting, Galetshoge called to offer me a job at the Department, which I declined. I was young and opinionated, disappointed that a community project had been rudely disrupted.” Two months later, she became the administrative secretary of the Ngwato Land Board. Her days of activism at Mmegi were cut short when she became a civil servant.