Inside Seretse’s secret

Lewanika Timothy | Monday September 30, 2024 10:30

Botswana’s independence was given on a silver platter, without a single stone thrown or the tiniest drop of bloodshed.

Candidly speaking, the British must have seen it as good riddance to finally let go of a colony that was a barren investment in the eyes of many; a colony in abject poverty with little to no natural resources. As was British policy back then, colonies were to serve as a fortune booster for the United Kingdom and Botswana was far from satisfying this criteria, at least from what met the eye.

As the shackles of colonial oppression fell off Bechuanaland’s wrists, Seretse Khama watched with a smile. More than just securing political triumph, he had blindsided a global power, played his cards close to his chest, and secured the future of generations to come.

The revelations are contained in Delusions of Grandeur, the epic narration of the pre- and post-independence economy penned some years ago by former Cabinet minister, lawyer, and business mogul, David Magang.

In 1965, De Beers’ supremo Harry Oppenheimer had whispered the presence of ‘special stones’ to Seretse, appraising him on a kimberlite pipe in Botswana that could be an economic game changer for the country. This was two years ahead of the official announcement of the presence of diamonds in the country, a well-kept secret that secured Botswana’s future.

Following Oppenheimer’s disclosure of diamonds in Botswana, historical annals have it that Seretse could only confide in Peter Fawcus, the Queen’s Commissioner to Botswana from 1963 to 1965. Fawcus had won over Seretse’s heart as a shrewd administrator who had the interests of Botswana at heart. He would later help Seretse to lay the pegs of public bureaucracy that shaped the government of 1966.

Fawcus too jealously guarded Seretse’s secret that Botswana had stumbled upon an Aladdin’s cave of gem-quality diamonds. If Fawcus had betrayed this trust and whispered it to Alec Douglas-Home at No.10 Downing Street, Botswana would in all likelihood still be Bechuanaland today. In 1967 Oppenheimer accredited the well-kept secret to the work of divine providence, explaining it as somewhat of a miracle that would help the country rise from the ruins of poverty.

“I cannot help feeling that somehow providence intended that this should be a highly successful country,” he said.

The story of Seretse’s secret goes even further than hiding the diamond discovery from the colonial masters. It is also about his long-term vision of shared mineral wealth for national benefit. The diamond kimberlite found in the Gammangwato cattle posts of Orapa could have provided Seretse with an opportunity to enrich himself and his tribe, enjoying the fruits alone with his kinsmen as was the case in other countries like the DRC.

Seretse took a different route and shaped Botswana’s economic development and global esteem as one of the few that broke the “resource curse”. Minerals which are a development precursor in many nations, have turned out to be a source of fragmentation and regression, hence the term “resource curse”. The shrewd management and selfless leadership of Seretse and co, however, steered the country in the best direction. Through its partnership with De Beers, the country would steadily rise to become an African jewel.

Magang apportions Botswana’s rise solely to meritocracy and the sound leadership of that first administration. According to Magang, Seretse managed to steer away from selfish political ambition and devised a strategy that would ensure an equal sharing of mineral fruits for the whole country.

Magang further recounts that Botswana’s diamond endowments were not an isolated blessing. Other minerals such as gold, silver, and asbestos had long been discovered before independence, however, in quantities that could not lure investors to the country. In fact, he says that “they existed in quantities that could not jolt the economy forward”.

To lay the matter even barer, at independence, the national population was 576,000 people with only about 30,000 people in formal employment. The economy’s cash cow was livestock which made up 90% of all imports. At independence, 50% of the budget’s recurrent expenditure was donor-funded.

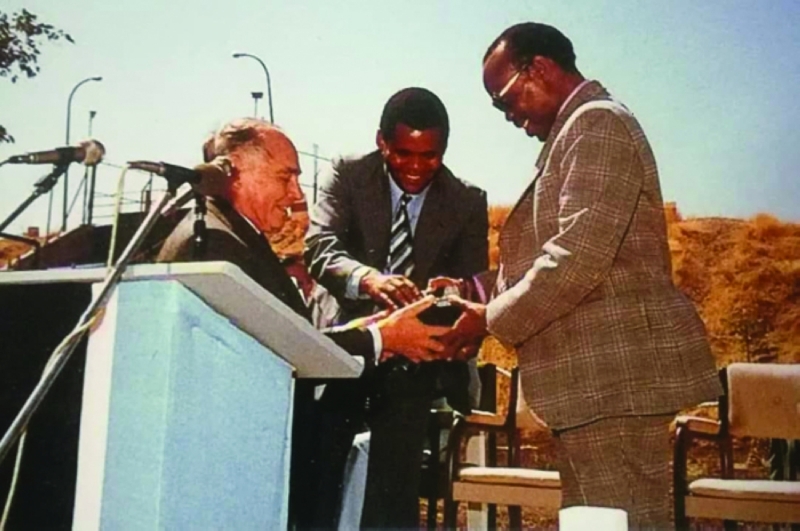

When Seretse took the oath of office in 1966, the task ahead was daunting and arduous. Even with the presence of diamonds in the country, the process of nation-building and setting up a developmental agenda that will stand the test of time, was the true test of leadership which Seretse successfully passed. His cunning ability to negotiate and lead had roots in his rare oratory skills and his mastery of English. His royal pedigree worked for his party as many could not distinguish between chieftainship and democracy. To many, the presidency was his birthright.

Despite the enormous privilege ascribed at birth by his royal background and his Oxford education, Seretse Khama maintained a down-to-earth posture, preferring to be seen as a servant rather than a master of the people.

He was a man of great humility, a royal who wanted to mingle with commoners on an equal footing. He valued collective wisdom as opposed to individual accolades. During his 14-year presidency, he strove to promote people-centred power. Seretse was a true keeper of secrets, a virtuous leader and a national hero.