Recently, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its report on the effects of climate change. Its conclusions were all too familiar – every region in the world is experiencing adverse impacts due to climate change.

And we need to urgently defuse the climate timebomb; for example, by phasing out the use of fossil fuels. It’s the same old climate change song – blame everything that is negative on climate change! But other factors may also be responsible in explaining what we are now observing in the world today.

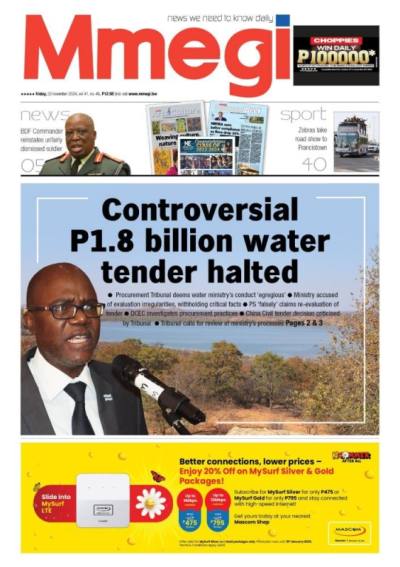

On page 24 of the March 24 issue of Mmegi, there was a photo of an empty looking Gaborone Dam taken in 2016.

The caption for the photo implied that an ‘intensification of climate change in the region’ was directly responsible for this state of affairs. But is this really true? To come up with answers to this burning question, we need first to look into the history of Gaborone, the capital of Botswana.

Right up to the year 1965, the former Bechuanaland Protectorate was administered from Mafikeng [then known as Mafeking] in neighbouring South Africa. At the time, it was probably one of the very few countries in the world to have an external capital. But as independence approached, it was decided to move the capital to within the boundaries of the protectorate.

However, there was much debate at the time as to where the capital should be located. In 1961, the Bechuanaland Protectorate Legislative Assembly recommended to Britain, the colonial power, that the new capital should be built at Gaberones, then a small village located along the Mafikeng-Bulawayo railway line.

One reason for this was that it would be close to South Africa from where most of the country’s imports originate even though at the time that country was ruled by the apartheid National Party. Lobatse was also considered, but the lack of water and the hilly nature of the surrounding country were seen as major obstacles to the development of the country’s largest town. And the British government expressed the view that Francistown would be a better place. But the Legislative Assembly’s recommendations were upheld, and in 1963 a start was made on the construction of the Gaborone Dam, while work started on the town in 1964.

The town planners of the day estimated that the town would accommodate, at most, no more than 25 000 people. It was planned to lie between the Village and the railway and so would occupy areas only to the east of the railway. The outer limit of the town would be marked by the Outer Ring Road – Nyerere Drive and Machel Drive – which passes the showgrounds, University of Botswana, the Avani Gaborone Hotel and Casino, and Middle Star Mall.

But the city fathers had overlooked the fact that in developing countries towns act as magnets for rural dwellers seeking jobs and riches. Although Gaborone was home to only some 3, 900 people in 1964, the town’s population in the early 1970s had already exceeded the planned maximum population and yet the town still continued to grow in leaps and bounds. So, to prevent the Gaborone Dam from drying up, in 1982, the dam wall was raised by eight metres to 25 metres, thus increasing the size of the dam to 19 square kilometres with a maximum capacity of 141 million cubic metres of water.

But to assure the capital’s water supply for years to come, the 370-kilometre North-South Carrier project was completed in 2000; this involved bringing water to Gaborone from distant Letsibogo Dam, on the Motloutse River near Selebi-Phikwe. In 2012, construction of the larger Dikgatlhong Dam on the Shashe River was completed and water from this dam now feeds into the NSC pipeline. But, despite all this, the supply of water to Gaborone still fell far short of the demand and this led to the drying up of the Gaborone Dam in 2016. Although this coincided with a drought period, as indicated before, other reasons, besides climate change, can help to explain this.

Firstly, Gaborone’s rate of population growth has exceeded all expectations and, at present, some 300, 000 people call Gaborone home – more than 10 times the predicted maximum population for the city. And the water is not only used for human consumption; industries also consume large quantities of the stuff. Furthermore, the neighbouring sprawling peri-urban villages of Tlokweng and Mogoditshane, together home to more than 120, 000 people, also tap water from the Gaborone Dam. Secondly, other places in the country would have been better for the site of the new capital. The Gaborone Dam lies on the Notwane River, a tributary of the Limpopo.

However, this river is small and more like a donga than a real river; at Riverwalk Mall in Gaborone, the Notwane is little more than ten metres wide. This means that only small amounts of water enter the dam when it rains. The catchment area [the area drained by the Notwane and its tributaries] of the Notwane is also relatively small and water is also extracted at places along its length by farmers. Francistown is located along the Tati River in the north east of the country. Although this river, like the Notwane, is a tributary of the Limpopo, it is a much larger river since it occurs further downstream.

At Francistown, the Tati is over 50 metres wide and its catchment area is much larger and extends northwards towards the Zimbabwe border. Hence, if a dam were built here it would fill quickly after heavy rains and would be most unlikely to dry up during severe droughts. The Shashe Dam, which is located on the Shashe River, 30 kilometres south of Francistown, has also never been in any danger of drying up.

The site of a dam is also important. Much of Botswana is flat and quite unsuitable for the construction of dams. At Gaborone, the Notwane valley is wide and flat which means that the dam itself is large but shallow.

In fact, most of the dam is less than five metres [5 000mm] in depth. Now we know that Botswana is a semi-arid country, which experiences high temperatures which frequently exceed 350C, especially between September and March. And during dry years, temperatures may top 400C. This, together with a low relative humidity, results in high rates of evaporation, or loss of water, from the dam.

The average annual rate of evaporation is about 2 000mm and, even in the wet season, evaporation losses usually exceed rainfall. So, doing some mathematics, we can see that the Gaborone Dam will most likely dry up completely within about two and a half years, assuming no inflow of water has taken place during that time [5 000mm /2 000mm]. And that is assuming that no water is actually used. So, we can see that in most years more water in the dam may be lost solely by evaporation than what is actually used. In contrast, the most suitable site for a dam is in a deep, narrow steep sided valley in a mountainous area. For example, in Lesotho, dams have been constructed along the tributaries of the Orange River in the Maloti Mountains. Since the water in these dams is very deep, it would take many years before it could all be evaporated.

For this reason, the Nywane Dam, near Lobatse, is better located since the Nywane River here flows through a narrow deep valley. However, the river is very small, and is a tributary of the Notwane, and so, little water would flow along it after heavy rains. In addition, some water may be lost due to leakages in pipes. In fact, some experts have estimated that the amount lost due to pipe leakages may be in the order of some 20% of the water extracted from our dams. In conclusion, we have seen that climate change alone cannot explain water shortages in the Gaborone area. Other factors include high rates of population growth, poor choice for the location of the country’s capital, poor siting of dams etc.

But on a more positive note – although the Gaborone Dam failed in 2016, in March the following year it filled completely and overflowed! Climate experts may tell us that droughts are becoming more severe, but in the past the country experienced even worse droughts – in the 1960s, and the six consecutive years of drought in the 1980s from 1981 to 1987!